As lacking as our history classes are, the curriculums never omit Western atrocities such as ethnic cleansing of Native Americans, slavery, and colonialism in Africa. However, rarely are the US's own attempts at colonialism in the Pacific taught. If mentioned at all, never do we hear the perspectives of the victims. Few Americans today know that the US conquest of Hawaii was no more dishonorable than the Western colonialism in North and South America or Africa, where countless kingdoms and empires were unjustly overthrown. Even fewer Americans are aware of our not-insignificant territorial possessions in the Pacific, and the fact that American Samoa remains in an essentially colonial status where residents are not granted US citizenship.

To better elucidate why the US must remove its influence from the Pacific and be prevented from carrying out the Pacific Pivot, we need look no further than our ignoble recent past in order to get a taste of what the future may hold unless the US is able to jettison its attachment to Western attitudes.

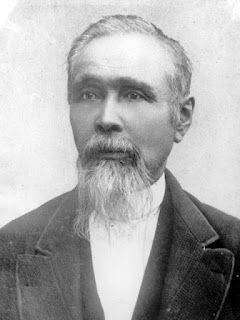

Until the average American is able to effortlessly side with King Kalākaua and Queen Liliʻuokalani over President William McKinley, until every statue and memorial of Commodore Perry is replaced by one honoring Ranald MacDonald, and until the US can demonstrate it has sincerely renounced its Western past by restoring Hawaiian sovereignty and voluntarily withdrawing its military presence from the Pacific, the US is unqualified to be a member of the Pacific community.

Table of Contents

Part 1Part 2

- VI. Twilight

- VII. Resistance

- VIII. The Pineapple Republic

- IX. Samoa

- Summary of Chapter 2

Part 3

- 3. Peak of US Colonial Hegemony: Spanish-American War to WWII

- I. Spanish-American War Overview

- II. Mahárlika: Haring Bayang Katagalugan

- III. American Resistance to the "White Man's Burden"

- IV. Philippine-American War: Continued Resistance to Colonial Hegemony

- V. US Colonization: Philippine Insular Government and Commonwealth

- VI. Anti-Colonial Resistance in Samoa

- VII. Hawaii: Post-Annexation

- Summary and Conclusion of Chapters 1-3

1. Japan-US History

While America started out as a group of British colonies united in a folkish struggle for independence from their colonial oppressor, the seeds of Western and Anglo-centric thinking planted by Britain did not vanish. Colonialism is quite profitable to the colonizer (and even if there is little profit, there is at least the "prestige" of being powerful enough directly exert influence on other nations), and with British influence removed from North America, a whole continent was open for the taking in the eyes of some US residents...

Many believed it was now the responsibility of the US to pick up where Britain left off as the primary bearer of Western Civilization in North America. After the US gained independence, the states continued ignoble practices established by the British, such as slavery and displacement of natives to make way for "white" settlers. But it was with the rise of "Manifest Destiny" (more aptly understood as an outbreak of "Chosenite Syndrome") in the 1840s that US politicians began taking conscious steps to modify US policy to more closely resemble the hegemonic system of Western powers—which Americans had fought so hard to destroy during the Revolutionary War.

The US's involvement in spreading Western hegemony in the Pacific Ocean began around 1852, when President Fillmore assigned Commodore Matthew Perry the task of "opening" Japan to Western trade, while Britain and other European powers were busy "opening" China via the Opium Wars. While this era of history is largely forgotten to the average US citizen (and never condemned with the same frequency as continental examples of Manifest Destiny), it is not-so-subtly known as the Century of Humiliation in China; and the treaties which Western powers forced China, Japan, and Korea to sign are referred to as the "Unequal Treaties". Following the "success" of Perry's mission, Japan eventually sided with the West and imposed Unequal Treaties of their own on China and Korea...

***

Earlier, in 1845, Commodore James Biddle had traveled to southern China to formalize a treaty allowing trade between the US and China, modeled after earlier British treaties. He then traveled to Japan and anchored two warships in Tokyo Bay, hoping to intimidate Japan into signing a similar treaty. The Japanese were not fazed, and informed him that future negotiations would have to be held in Nagasaki—the only city open to foreigners.

Perry, determined to neither repeat the failure of Biddle nor respect Japan's policy of isolation, brought twice as many warships into Tokyo Bay. To intimidate the Japanese, Perry was quick to employ the jingoistic "gunboat diplomacy" that the US continues to practice to this day—firing his cannons and threatening to invade unless his letter containing US demands was received directly by a high ranking Japanese official. After the letter was received, Perry promised to return in a few months to receive Japan's reply.

Unfortunately for Japan, not only were its military defenses woefully inadequate to defend themselves against a potential invasion, but the shogun died only days after Perry left. The new shogun was sickly and weak-willed, so power temporarily devolved to the Council of Elders. Also crippled by indecisiveness, the Council decided to poll the opinions of the every daimyō, hoping that the backing of a majority opinion would absolve them of responsibility should they make a disastrous choice. Demonstrating the weakness of democracy when faced with making such a crucial decision, the results of the poll were evenly split between opposing the US demands and accepting them!

Upon hearing that other Western powers were also attempting to ratify treaties with Japan, Perry came back a few months later, eager for a reply. The Japanese attempted to stall Perry by proposing a number of different cities to sign the treaty in (while Perry was dead-set on the capital). This infuriated Perry, who proclaimed that the US would declare war on Japan and bring over 100 ships within 20 days notice (despite the fact that the US Navy did not even have this many ships) if negotiations did not proceed immediately. Japan, not wanting to suffer the same fate as China (which was being ravaged by on-going wars started by Westerners), conceded. The Kanagawa Treaty was signed in 1854 and led to numerous additional treaties by the US and Western powers with Japan in the following years.

Before landing in Japan, Perry had first gone to he Ryukyu Islands (an independent kingdom at the time) and demanded they be opened to US trade under the threat of direct military intervention (resulting in the Lew Chew Compact). He then traveled east to the island of Chichijima, where a US settlement had been established by Nathaniel Savory in 1830. Eager to expand US territory, Perry created a draft organizing a government for the island and appointed Savory as the governor of the "Colony of Peel Island". This colony was never formally recognized by the US government, and Japan integrated the islands into their nation in 1862.

However, the US government never forgot the symbolism behind Savory's colony. After WWII, the Ryukyu and Nanpo Islands came under US military governance for over two decades. On Chichijima, the US only allowed 126 individuals of Western ancestry to return to the island (which had previously been evacuated of all inhabitants by Japan in 1944).[1] And to this day, Okinawa island (the largest in the Ryukyu chain) remains a major US military base.

[1] Robert D. Eldridge. Iwo Jima and the Bonin Islands in U.S.-Japan Relations: American Strategy, Japanese Territory, and the Islanders In-Between. Marine Corps University Press, 2014. See Chapter 5 (pg 192-233).

https://www.usmcu.edu/sites/default/files/MCUPress/IwoJimaBoninIsland.pdf

***

The success of Perry's mission created chaos in Japanese society, eventually resulting in the Meiji Restoration in 1867. Although nominally under the rule of the Emperor, Japan became controlled by a group of oligarchs who opted to gradually implement a constitutional monarchy and representative voting system modeled after Western nations, in the hopes of gaining a seat at the table of Western powers.

Meaning "enlightenment," the Meiji period saw Japan adopt many of the cultural and economic practices which the West had adopted during the so-called "Enlightenment Era". One of the most notorious Japanese advocates for Westernization was Yukichi Fukuzawa. A member of the pro-Western intellectual society Meirokusha, Fukuzawa rose to prominence after publishing An Outline of a Theory of Civilization in 1875. In this book, Fukuzawa presented a classification of civilization which mirrored the Western worldview: Africa was the least civilized, Asia was intermediate, and Europeans were at the pinnacle. Urging that Japan become more "civilized," his views became widespread in Japan.

Often attributed to Fukuzawa, an anonymous editorial titled Datsu-A Ron (often translated as "Leaving Asia") was published in 1885. Scholars believe the essay was a response to the failed pro-Western Gapsin Coup in Korea. The Datsu-A Ron succinctly captures the Meiji era opinion that the non-Westernized cultures of China and Korea are too inferior to offer resistance to the West, and that Japan should Westernize in order to become a world power.

"Once the wind of Western civilization blows to the East, every blade of grass and every tree in the East follow what the Western wind brings. The spread of civilization is like the measles. In my view, these two countries [China and Korea] cannot survive as independent nations with the onslaught of Western civilization to the East. It is not different from the case of the righteous man living in a neighborhood of a town known for foolishness, lawlessness, atrocity, and heartlessness. His action is so rare that it is always buried under the ugliness of his neighbors' activities. We do not have time to wait for the enlightenment of our neighbors so that we can work together toward the development of Asia. It is better for us to leave the ranks of Asian nations and cast our lot with civilized nations of the West. Those [who] are intimate with bad friends are also regarded bad, therefore I will deny those bad Asian friends from my heart." –Leaving Asia

The oppressed had now started on a path to become the oppressor. During the Meiji period, Japan joined Western powers in subjecting China and Korea to "Unequal Treaties," and allied with the Western powers during the Boxer Rebellion.

"if we take the initiative, we can dominate; if we do not, we will be dominated" –Shimazu Nariakira

This trend would not be reversed until WWII, when the Co-Prosperity Sphere offered a chance for west coast Pacific nations to join in an anti-Western alliance to overthrow colonial control. While Western powers were victorious in the Pacific after WWII, Japan's actions helped speed up the release of Pacific nations from Western colonial control. Beyond this, some anti-Western attitudes have continued into the 21st century—on both sides of the Pacific.

The Last Samurai: the most famous 21st century American portrayal of this era in pop culture depicts a fictional American hero who sides with the Japanese forces who rebel against the Meiji Westernization. In reality, many of the rebelling samurai were traditionalists who were unwilling to see society move in any new direction, regardless of whether or not the changes had any merit. Additionally, the upgrading of the Japanese military was a necessary act in order for Japan to have any hope of defending itself against Western powers (although such a military upgrade should have by no means necessitated Westernization of the culture and government as well). Historical details aside, the popularity of a film where an American soldier who is critical of Manifest Destiny and willing to fight so that it does not creep into Japan shows us just how far US culture has drifted away from Perry's Western ideals and towards the America embodied by MacDonald's (see below).

***

Just as there have always been "two Japans"—one pro-Western and one heroically anti-Western—so too was there a similar split within the US. In the context of early Japan-US relations, the anti-Western and authentically American spirit is exemplified by a virtually unknown American: Ranald MacDonald. Born in Fort Astoria, Oregon, MacDonald was the son of a Chinook princess and a Scottish immigrant, and became fascinated with the land across the Pacific at an early age.

After quickly growing tired of training to become a banker, a young MacDonald resolved that he would one way or another visit Japan—despite knowing full well that any foreigners could be executed or imprisoned due to Japan's strict policy of isolation. After working for years as a sailor, in 1848 he managed to convince his ship's captain to drop him off on a small boat near Hokkaido island. In stark contrast to Perry's displays of military dominance, MacDonald decided to shipwreck himself and humble himself to whatever fate awaited him, but was hopeful that he could start a friendly dialogue between citizens of the east and west Pacific basin.

"My plan was to present myself as a castaway ... and to rely on their humanity. My purpose was to learn of them; and, if occasion should offer, to instruct them of us." –Ranald MacDonald

MacDonald was captured and taken to Nagasaki, where he was placed under house arrest in a local temple. There he quickly befriended the guards and became the first person to teach English in Japan. Among his students was polyglot Moriyama Einosuke, who served as the lead translator during Perry's negotiations. In 1849, a US ship came to Nagasaki to collect imprisoned US sailors who had been shipwrecked, and MacDonald was made to go with them. After leaving Japan, MacDonald traveled throughout Oceania before coming back to North America.

Shortly before Commodore Perry's mission, Congress took testimony from MacDonald regarding his experience in Japan. Perhaps to their disappointment, MacDonald spoke of Japan's high level of civility (in his estimate, Japan was much more literate and orderly than the US!) Although imprisoned during his stay in Japan, MacDonald looked back fondly on his experience, recalling a few years before his death:

"After having girdled the globe and come across people many, civilized and uncivilized, there are none to whom I feel more kindly than to my old hosts of Japan."

2. Colonialism in Hawaii, Samoa, and beyond.

I. Introduction

Drunk on jingoism from the Mexican-American War, the US elected Franklin Pierce as president in 1853. One of the most thoroughly pro-Western presidents the US has ever had the misfortune of having, Pierce supported the expansion of slavery into the western territories, was sympathetic to terrorist William Walker's attempts to seize control of various Latin American nations, and was a vocal supporter of US territorial expansion. During his presidency, the Guano Islands Act was passed in 1856. This act provided the legal framework for much of the US's colonial aggression in the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea, by allowing US citizens and corporations to take possession of 'unclaimed' islands containing guano (a lucrative source of gunpowder and fertilizer). What "unclaimed" really meant, of course, was unclaimed by Western powers (who were able to defend their claims through military force).

Although most of the islands which were claimed using the Act as justification really were uninhabited, focusing on this fact misses the big picture. As a direct effect of the Act, the territorial status of "Insular Area" was introduced into the US government. Previously, all territory gained by the US was considered a direct part of the nation with the eventual goal of complete integration via statehood. Insular Areas, however, were to be held as virtual colonies with minimal opportunity for further integration into American society. It was with this Act that the US government openly declared to other Western powers that they were entering the game of colonial expansion. Other writings and acts of legislation (e.g. Ostend Manifesto, annexation of Hawaii, Spanish-American war, etc.) never allowed themselves to be constrained by the Act's condition of uninhabitance, of course...

The Guano Islands Act remains in force today, and the US still has territorial claims originating from it. To give one example, Navassa Island in the Caribbean was claimed by the US in 1857 despite being claimed by Haiti since 1801. The US government continues to claim Navassa Island (with Haiti continuing to dispute this claim). Most islands claimed under the act were islands in the Pacific—and many proved to be of great importance as military bases.

Today, the inhabited US Insular Areas are American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands. Additionally the Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau are formally considered "Freely Associated States". Not granted US citizenship at birth, these 3 nations are essentially in suzerainty or quasi-colonial protectorates of the US. Residents of these nations get some special privileges in the US over complete foreigners, but they must go through the same process in order to obtain lawful permanent resident status and citizenship. (For reference, the formal Spanish name for Puerto Rico (whose residents do get US citizenship) is the "Free Associated State of Puerto Rico"). American Samoa is the only US territory which can unambiguously be considered a colony today. People born in American Samoa do not get automatic citizenship, but instead are only given the status of "US Nationals." Uninhabited Insular Areas which are of high military significance include Johnston Atoll, Midway Island, and Wake Island.

The US began chipping away at Hawaiian sovereignty using the Guano Islands Act—claiming Midway Island, Palmyra Atoll, and French Frigate Shoals (Kānemilohaʻi). Hawaii is the US's largest territory in the Pacific, both in terms of population and land area. It is also the only one which has become a state (the rest retain the status of Insular Area, a remnant of their colonial past). As such, Hawaii is the nucleus of US power in the Pacific, and study of its past and present deserve special attention.

***

Hawaii's relationship with the West was on rocky ground from the very beginning.

In 1776, British explorer James Cook began his third voyage of the Pacific with the goal of mapping the Northwest Passage—a hypothesized path connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans north of Canada. While traveling north towards the Bering Strait, in 1778 he became the first Westerner to land in Hawaii. After a brief survey of the islands, Cook departed and continued his journey. Failing to to pass through the Bering Strait, Cook returned to Hawaii in 1779 to resupply and repair his ships.

After making landfall on Hawaii Island, Cook's squadron was greeted by Hawaiians offering gifts. A priest approached Cook and personally escorted him ashore to take part in the Makahiki harvest festival. Cook stayed for a pleasant month before departing to continue his journey. However, immediately after leaving, the mast of one of his ships broke and he returned to Hawaii for repairs. The damaged mast would soon prove to be the least of Cook's problems.

Although history is unclear as to what happened immediately after Cook's return, tensions between Cook's group and the Hawaiians quickly rose. In retaliation, the Hawaiians stole one of Cook's small lifeboats, and threats of armed force were unable to secure its return. In order to "barter" for the return of his boat, Cook decided to take hostages (a tactic which he had employed in other Pacific islands). Underestimating the the Hawaiians, he decided he could get away with kidnapping King Kalaniʻōpuʻu (ruler of the single island of Hawaii)!

Cook, along with a group of armed men, kidnapped Kalaniʻōpuʻu while he was sleeping. Confused (most likely due to the friendly reception Cook had been given a month earlier), Kalaniʻōpuʻu at first put up no resistance. Thankfully his wife, Kānekapōlei, realized Cook's plan was nefarious and alerted the local officials and townspeople.

As they neared the shore, a group of thousands of Hawaiians had gathered around the scene. By this point, the King realized what was occurring and refused to follow Cook any further—sitting on the ground in protest. Irate, Cook ordered his men to raise their guns at the crowd, and grabbed the King in an attempt to force him to his feet. Prince Kana'ina attempted to intervene, but was slapped by Cook's sword. Unable to tolerate Cook any longer, the King's attendant, Nuaa, with assistance from Kana'ina, admirably killed Cook with a dagger, putting an end to his wake of violence across the Pacific. A skirmish ensued in which a number of Cook's men and Hawaiians were killed, after which Cook's men were routed. The Hawaiians gave Cook a funerary rite reserved for those of high status (although the British sailors interpreted these rituals as malevolent acts of defilement and barbarism), after which his remains were returned to the crew.

II. Unified Kingdom of Hawaii

According to Hawaiian legend, whoever was able to lift the massive Naha Stone possessed the spiritual strength necessary to unify the Hawaiian islands (some versions of the legend prophesied that this united kingdom would extend as far as Aotearoa). Over the centuries, many had tried, but exceedingly few had succeeded. Even so, none of them had actually accomplished the great feat of unifying the islands—that is, until Kamehameha the Great arrived on the scene.

As a youth, word of Kamehameha's strength, charisma, and quality of character quickly reached the attention of the island's high priests, who received visions that Kamehameha was destined to be king. At their urging, he traveled to the location of the Naha Stone accompanied by the high chiefs of Hilo. At first, the local rulers were incredulous, as they believed Kamehameha stood no chance to move it because, while being of royal blood, he did not belong to the Naha dynasty (after whom the stone was named). Undeterred, Kamehameha grasped the stone and moved it after a tremendous effort.

In awe, the high chiefs humbly conceded that Kamehameha's feat was indeed an indicator that he belonged to the highest levels of nobility, irrespective of his ancestry. Prince Keaweokahikona (who was rumored to be the only other living individual able to move the stone) recognized that this meant Kamehameha's spiritual bearing was more similar in quality to his own than any members of his own family. Keaweokahikona confided this to Kamehameha and pledged his loyalty and service in any of Kamehameha's future endeavors.

"As you have moved the Naha Stone today, which no other chief could have done ... My spear is for you, to you also will I give the spears of my band of warriors. Therefore, let us be as brothers..." –Keaweokahikona

Upon King Kalaniʻōpuʻu's death in 1782 he was succeeded by his son Kīwalaʻō, while Kamehameha inherited the most prestigious religious position on the island. The two hated each other, and the deeply divided loyalties of the island's chiefs and priests led to a civil war.

As Keaweokahikona had pledged loyalty to Kamehameha, he was fighting against his father and many others in his family who tried to uphold the traditional social order. Keaweokahikona's family attempted to sow distrust between the two, telling Kamehameha he was disloyal, but Kamehameha deeply felt the sincerity with which Keaweokahikona had pledged his services, and did not believe a single word. Keaweokahikona's family subsequently had him poisoned, and Kamehameha used his spear in all subsequent battles to carry on his memory.

Always by Kamehameha's side was Kekühaupi‘o, a renowned warrior who trained Kamehameha in martial arts and served as one of his closest advisors and generals. In no small part to Kekühaupi‘o's ability to train Kamehameha's troops, Kīwalaʻō was killed in the Battle of Mokuohai roughly one year after he had become king. In the aftermath of this battle, hostilities briefly wound down, and Hawaii Island found itself divided into multiple parts. Kamehameha's major foe on Hawaii Island was now Keōua Kuahuula, Kīwalaʻō's brother. For the next decade, various indecisive skirmishes were fought between both sides.

In 1790, Maui Island was visited by Westerners. Ending up even more disastrous than Captain Cook's visit, after ship captain Simon Metcalfe noticed one of his skiffs was missing (and presumed stolen), he massacred over 100 Mauians in revenge. Previously, Metcalfe had tortured Prince Kameʻeiamoku (one of Kamehameha's most trusted allies) while at Hawaii Island. After learning of the massacre, Kameʻeiamoku swore he would have no mercy on the next Western ship to anchor itself in Hawaii. It just so happened that Metcalfe was traveling with another ship, captained by his son. Kameʻeiamoku's troops killed every person on this second ship, except for a man named Isaac Davis. To investigate the whereabouts of his other ship, Metcalfe returned to Hawaii Island and dropped off crew member John Young to investigate. Young was taken prisoner, and Metcalfe departed after two days, stranding Young on the island.

Young and Davis grew fond of life in Hawaii—refusing to return to Britain when Captain Vancouver came to Hawaii in 1793 and offered to take them back. Demonstrating their willingness to integrate into Hawaiian society (and the Hawaiians' willingness to welcome them), they spent the rest of their lives in Hawaii, becoming close advisors to Kamehameha and even marrying princesses. This hearkens back to Ranald MacDonald's positive sentiment about cultural exchange—and indeed, to the spirit of the First Thanksgiving. Integration in its truest sense involves both newcomers learning from the culture of the natives, and natives learning from the culture of the newcomers (as opposed to assimilation, where natives impose their culture on the newcomers, regardless of the native culture's flaws or the merits of the newcomers' cultures). The cultural exchanges that initially took place in New England, Japan, and Hawaii could have each been beautiful starts towards dismantling the violent grasp of Western colonial hegemony—yet imposers of Western Civilization nipped these opportunities in the bud each time they occurred.

***

Eventually, Kamehameha learned his foes had allied with King Kahekili II of Maui, and temporarily turned his attention away from Hawaii Island. With the cannons acquired from Metcalfe's ship, and with the assistance of Young and Davis, Kamehameha routed much of the Mauian forces in the Battle of Kepaniwai (1790). Returning to Hawaii Island to stave off a surprise attack by Keōua Kuahuula, Kamehameha received favorable help from an erupting volcano, which killed 2/3s of Keōua Kuahuula's troops. Weakened and demoralized, Keōua Kuahuula attempted to have a meeting with Kamehameha, but was killed en-route, solidifying Kamehameha's control over Hawaii Island in 1791.

King Kahekili II died in 1794, but not before organizing his confederacy of Kauai, Maui, and Oahu Islands into a strong military force. After a decisive victory in the naval Battle of Kepuwahaʻulaʻula, Kamehameha severely weakened the Kauai-Maui-Oahu alliance, and, taking advantage of the war of succession which erupted after Kahekili II's death, landed in Oahu. Culminating with victory in the Battle of Nuʻuanu Pali, by 1795 Kamehameha controlled every island except for Kauai. After a number of failed invasion attempts, King Kaumualii of Kauai agreed to have his kingdom annexed into Kamehameha's realm in 1810. Hawaii was now unified into a single kingdom for the first time in its history.

Members of Kaumualii's government were angered upon learning of the surrender, and planned to poison him at a feast. Isaac Davis (who had by this time been appointed as governor of Oahu) learned of this plot, and informed Kaumuali. Unfortunately, the poison was given to Davis instead. John Young was appointed as Governor of Hawaii Island in 1802, serving until 1812. He adopted Isaac Davis's children after he was murdered and continued to be a well-respected citizen of Hawaii up to his death in 1835.

Unification seemed to have come just in time. By 1815, a Russian speculator began a plot to stake a colonial claim on the islands before Britain and other Western powers were able to do so. Attempting to reopen old wounds, Kaumualii (who was allowed to remain governor of Kauai Island after its integration into the Kingdom of Hawaii) agreed to let the Russians establish a protectorate over Kauai! Russian-employed trader Georg Anton Schaeffer quickly got to work building three forts on Kauai, and was convinced by Kaumualii that the superior military technology of the Russians would be able to quickly conquer the rest of the islands. Once word got out to both Schaeffer's superiors and the Hawaiians that he was overstepping his authority (his original mission was simply to receive compensation for shipwrecked goods, and the Tsar explicitly rejected the idea of a protectorate), the Russians were expelled from the island. (For his treason, King Kamehameha II placed Kaumualii under house arrest in 1821.)

***

Throughout his reign, Kamehameha the Great implemented a unified legal code for the Kingdom, improved the infrastructure of the islands, and brought an end to the centuries of war which had plagued the islands. He attempted to foster friendly diplomatic relations between Hawaii and America, European powers, and other Pacific nations—while also forbidding foreign speculators from owning land in Hawaii. One of his most memorable legal codes was the Law of the Splintered Paddle, basically a golden rule of sorts which made it made it every Hawaiian's duty to treat strangers with kindness. It is said that Kamehameha had originally formulated this principle during the war, when he attempted to kidnap non-combatant citizens living in his opponent's land in order to sacrifice them. After getting his foot stuck in a reef and becoming immobilized, one of these citizens hit him on the head with a paddle with such a force that it broke, but decided to spare his life. This incident greatly humbled Kamehameha, and seems to have toned down his desire for sacrifices.

Upon his death in 1819 Kamehameha's remains were buried in a secret location which has been lost to the ages.

III. The Beginning of the End

Although by most accounts Kamehameha I was wise and a talented statesman, he was too charitable in his estimation of the intentions of some of the Western visitors to Hawaii... Two of Kamehameha's trusted military advisors, Englishman George Charles Beckley and Scotsman Alexander Adams, were not as keen to integrate into Hawaiian society as Isaac Davis and John Young seemed to be. Both men claimed to have created the so-called Hawaiian flag (a variant of which is the state flag of Hawaii today).

One story of its origin states that Kamehameha frequently flew British and American flags over his home. While he may have interpreted flying foreign flags gifted to him by diplomats as a friendly act of diplomacy, both the Americans and British believed a flag signaled that Hawaii was under that nation's sphere of influence. To show Hawaii's "neutrality" during the War of 1812, Adams/Beckley created a flag which combined aspects of both the American and British flags. This apparently satisfied Kamehameha, who made it the official flag of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

This flag foreshadowed the beginning of the end of Hawaii as an independent nation, and its descent into the Western sphere of control... Decades prior during the war of unification Kamehameha had used a very different flag as his personal standard. Today, its design is commonly called the Kanaka Maoli, and has become a popular symbol among Hawaiians critical of Western rule. The original Kanaka Maoli is said to have been destroyed when British Captain George Paulet launched a 6-month-long military occupation of Hawaii in 1843, during which he destroyed every Hawaiian flag he found.

***

After Kamehameha I's death, his young son Kamehameha II formally became king, but Kamehameha I's wife Kaʻahumanu quickly declared herself co-regent and wielded most of the power during Kamehameha II's short reign. Kaʻahumanu, along with one of Kamehameha I's other wives, Keōpūolani (daughter of Kīwalaʻō), used Kamehameha II as a pawn to disrupt the traditional social and religious order and disempower the priest class. While this was not necessarily a bad thing in and of itself (for example, the grand taboo which Kamehameha II broke was allowing men and women to eat together), it seems that Kaʻahumanu had been conspiring with Western missionaries to cause chaos on the islands. The first missionaries were welcomed a few months after Hawaiian religion imploded, in 1820. (It is said that Alexander Adams was present to welcome the first missionaries and personally convinced the King to allow them to conduct their business on the island).

Among the first royal family members to convert to Judeo-Christianity, Keōpūolani died in 1823, but not before adopting Western clothing, manners, and attitudes.

"Jehovah is a good God. I love him and I love Jesus Christ. I have given myself to him to be his. When I die, let none of the evil customs of this country be practiced. Let not my body be disturbed. Let it be put in a coffin. Let the teachers attend, and speak to the people at my interment. Let me be buried, and let my burial be after the manner of Christ's people. I think very much of my grandfather, Kalaniopuʻu, and my father Kiwalaʻo, and my husband Kamehameha, and all my deceased relatives. They lived not to see these good times, and to hear of Jesus Christ. They died depending on false gods. I exceedingly mourn and lament on account of them, for they saw not these good times." –Keōpūolani.

(Do you think Jesus would have believed Western colonial hegemony signaled "good times"?)

Fond of the luxurious gifts that the British had given him, Kamehameha II traveled to London in 1824 to tighten diplomatic ties between Hawaii and the UK. After the King had departed on his voyage, Kaʻahumanu publicly revealed her religious conversion to Protestantism and encouraged her subjects to convert as well—going so far as to remodel Hawaiian laws after the Ten Commandments and other Old Testament values... Kaʻahumanu's brother, Hawaii Island Governor Kuakini, even changed his name to John Adams (after US president John Quincy Adams) and advocated Hawaiians to follow his lead to adopt Western customs and names.

While in London, Kamehameha II contracted an illness and died before he was able to meet King George IV. Inheriting the throne at age 12, Kamehameha III was under Kaʻahumanu's thumb until her death in 1832. During Kaʻahumanu's 'reign', she banned Catholicism in Hawaii in 1830 and established a trade agreement with the US in 1826.

***

Kamehameha III had rebelled against his mother and remained fond of pre-Western Hawaiian culture as a teenager, but by his 20s, he seems to have given up any hope to reverse the Westernization process that was rapidly unfolding in front of his eyes.

In 1838, Keōpūolani's husband Hoapili managed to convince missionary William Richards to act as a political advisor and tutor for Kamehameha III, and Richards instructed him in the principles of Western government, economics, and history. In 1840, Hawaii degenerated from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy under the Constitution of 1840, which also established an elected legislative body (which was further strengthened in the Constitution of 1852). Although perhaps resigned to accepting the Westernization of Hawaii's culture, Kamehameha III remained committed to the idea that Hawaii should remain an independent nation, and in 1842 he sought formal recognition of his kingdom from the UK, France, and US.

Ironically, instead of Western governments acting more benevolently towards Hawaii for its Westernization, their antagonism only increased. In 1839, the French had threatened to declare war on Hawaii if the ban on Catholicism was not reversed (the ban was quickly undone). Reminiscent of the actions of the rogue Russian Georg Anton Schaeffer just three decades earlier, British Captain George Paulet arrived in 1843 to investigate claims that British subjects in Hawaii were being harassed. Paulet demanded to speak directly with the King, refusing to speak to the King's appointed envoy, American Gerrit P. Judd. Perhaps being driven by the desire to assert British dominance on Hawaii before any other states formally recognized its independence, Paulet presented the Hawaiians with a strict list of demands, and then invaded the islands when the demands were not met.

Once news reached Admiral Richard Thomas, he traveled to Hawaii and restored Kamehameha III to the throne on July 31, acknowledging the Kingdom's independence. July 31 became a holiday known as Restoration Day in Hawaii, and Paulet apparently faced no punishment. France and the UK issued a joint proclamation on November 28, 1843 formally recognizing Hawaiian sovereignty (this date became celebrated as Independence Day). The US followed with their own proclamation on July 6, 1846. Hawaii became the first Polynesian nation to have its sovereignty recognized by the West, despite the fact that other sovereign kingdoms were strewn throughout the Pacific.

"Her Majesty the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty the King of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiian Islands) of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations, have thought it right to engage, reciprocally, to consider the Sandwich Islands as an Independent State, and never to take possession, neither directly or under the title of Protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed." –1843 Anglo-French Proclamation

Continuing the descent into Stockholm Syndrome that began with the flag of Hawaii, there is something quite depressing about the fact that 'Independence Day' was based on a date set by Western powers, rather than the date Kamehameha I had completed the unification of the islands!!! In American culture, July 4, 1776 holds an almost religious significance. Very few Americans realize we did not formally receive independence until September 3, 1783 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. This is because, to us, 1783 was just a formality and the US was indisputably born when the Spirit of '76 swept across the land. Let us hope that when Hawaii signs its declaration of independence in the future, Hawaiians will celebrate the date of its signing, not the date of formal recognition by outside powers!

Of course, this recognition of sovereignty did not last long. In 1849, French admiral Louis Tromelin came to Honolulu and demanded the King accept a list of demands (deja vu). After waiting three days, the French captured a fort in Honolulu, destroyed the weapons and cannons, ransacked government and private property, and even stole the King's yacht. After a two week occupation, Tromelin left. Despite international pressure from the UK and US, the French government refused to pay for the damages.

With the implementation of the Hawaiian Constitution, many government positions had become dominated by Westerners, especially US citizens. By the early 1850s, the increased number of ships sailing to Hawaii from the US west coast brought yet more unwelcome gifts. Smallpox ravaged the islands, and some glory seekers who struck out in the California Gold Rush decided test their luck at overthrowing the Hawaiian government. Such a practice was commonly known as filibustering, and, thankfully, the plot fell apart without much effort. However, Westerners in the Hawaiian government used the filibustering attempt to push the idea that Hawaii should be annexed into the US, thereby rendering it "safe" from future attempts at filibustering. One of the strongest voices for annexation was Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs Robert Crichton Wyllie. (Previously, Gerrit P. Judd had advocated annexation after Tromelin's invasion, but this did not gain much support). Despite objections by the British and French consuls in Hawaii, by August 1854 Wyllie had drafted a treaty of annexation with US agents. Thankfully, this treaty did not gain much traction in the US Congress. Kamehameha III died in December 1854.

IV. A Brief Reprieve

Hawaii's descent into the abyss was temporarily alleviated when Kamehameha IV attempted to put the brakes on Westernization. Before ascending to the throne, Kamehameha IV had spent much of his youth traveling throughout Europe and the US. He was accepted and well-received by autocratic states, but was bombarded with racism while visiting the US. These first-hand experiences caused him to immediately put an end to any discussions of annexation by the morally-inferior US.

"I found he was the conductor, and took me for somebody's servant just because I had a darker skin than he had. Confounded fool;. the first time that I have ever received such treatment, not in England or France or anywhere else........In England an African can pay his fare and sit alongside Queen Victoria. The Americans talk and think a great deal about their liberty, and strangers often find that too many liberties are taken of their comfort just because his hosts are a free people." –Kamehameha IV reflecting on his experience of being harassed for being a "colored" man on the wrong train car—not long after he had just had a meeting with the President and Vice President!

Although many Americans may like to think our democratic form of government has somehow made our society more "enlightened" or just in comparison to autocratic states, a brief survey of our history shows democracy has, if anything, enabled extreme prejudice and misfortune for those subject to the will of the tyrannical majority. Kamehameha IV's diary entry expressing his shock at the racist gulf separating the UK and US captures an almost identical sentiment as his American contemporary Frederick Douglass:

“Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle. I breathe, and lo! the chattel becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door—I am shown into the same parlour—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended… I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, ’We don’t allow niggers in here!'”

(At the time of writing this, Douglass was still formally considered someone's property who had illegally escaped. Sympathetic individuals in the UK raised enough money to buy his liberty from his owner so he would not be re-enslaved once returning to the US).

"Educated by the Mission, most of all things dislikes the Mission. Having been compelled to be good when a boy, he is determined not to be good as a man." –Westerner Gerrit P. Judd, criticizing Kamehameha IV for his distaste of Western indoctrination.

Demonstrating that he was not merely a nativist who was hostile to all things foreign, Kamehameha IV made Christmas a formal holiday in Hawaii (despite protests from Bible-thumping missionaries who actually disliked Christmas since it was based on earlier "pagan" solstice celebrations!). Additionally, he married Emma Rooke in 1856, despite protests from ethnocentric Hawaiians who believed her mixed heritage (she was the granddaughter of John Young) made her unfit to be queen. (These ethnocentrists somehow missed the ironic fact that countless "unmixed" members of the royal family had actively encouraged Western hegemony on Hawaii over the previous decades...) After Kamehameha IV's death, Emma remained a prominent voice in Hawaiian politics.

"We have yet the right to dispose of our country as we wish, and be assured that it will never be to a Republic!" –Queen Emma

Tragically, like many other members of Hawaiian royalty, Kamehameha IV died young. He was only 29. During his short reign, he began to reorganize and upgrade Hawaii's military, attempted to implement public health initiatives (many of which were struck down by the elected legislature), began agricultural improvement programs, attempted to limit the influence of US citizens and other Westerners within the Hawaiian government, and formally expanded Hawaiian territory in order to guard against US encroachment. He annexed the uninhabited islands of Laysan (Kauō) and Lisianski (Papa‘āpoho) in 1857, and Palmyra Atoll in 1862.

Most interestingly, citizens of the island group of Sikaiana in the Solomon Islands petitioned the King for annexation into Hawaii. Although it seems they were never formally integrated into Hawaii (on the other hand, the Republic of Hawaii continued to claimed these islands as late as 1895), some Sikaianans to this day maintain that they are Hawaiians. Looking back, it was prophesied in Kamehameha I's time that the Kingdom of Hawaii would one day extend as far as Aotearoa; and looking forward, the events with Sikaiana foreshadowed King Kalākaua's attempts to establish an anti-Western Pacific Empire in the 1870s.

***

In 1863, Kamehameha IV's brother ascended to the throne as Kamehameha V. Having traveled abroad with his brother during his youth, Kamehameha V continued his brother's policy of being on guard against Westernization. Perhaps influenced by witnessing the disastrous effects democracy had wrought on US society in comparison with states that remained autocratic, Kamehameha V refused to swear an oath to govern by the pro-democratic 1852 constitution and instead called for the drafting of a new one. After members of the constitutional convention failed to come up with terms agreeable to the King, he dissolved the convention and drafted it personally, with assistance from his advisors. Some of the changes in the 1864 Constitution included: abolishing the office of kuhina nui (co-regent), changing Hawaii's legislature to a unicameral system, and making requirements to vote more strict. Although it was a far cry from the days of true (absolute) monarchy under Kamehameha the Great, this constitution was a much-needed breath of fresh air for Hawaii.

Kamehameha V was a well-loved monarch, and Hawaii prospered under his leadership. Hawaii continued to remain a popular tourist destination for Americans. Despite being outspokenly pro-Western-imperialism at the time, even Mark Twain couldn't help but admire Kamehameha V:

"He was a wise sovereign; he had seen something of the world; he was educated & accomplished, & he tried hard to do well by his people, & succeeded. There was no trivial royal nonsense about him; He dressed plainly, poked about Honolulu, night or day, on his old horse, unattended; he was popular, greatly respected, and even beloved." –Mark Twain

As king, Kamehameha V became the first monarch to outspokenly encourage de-Westernization of Hawaiian culture—lifting the ban on ancient Hawaiian spiritual practices and the study of non-Western medicinal practices. While he and Kamehameha IV's anti-Western gains would only be temporary, their reigns served as an inspiration for Hawaiians and an object of disgust for Westerners for decades to come:

"It is true that the germs of many evils of Kalakaua's reign may be traced to the reign of Kamehameha V. The reactionary policy of that monarch is well known. Under him the "recrudescence" of heathenism commenced, as evidenced by the Pagan orgies at the funeral of his sister. Victoria Kamāmalu, in June, 1866, and his encouragement of lascivious hula hula dancers and the pernicious class of Kahunas or sorcerers. Closely connected with this reaction was a growing jealousy and hatred of foreigners." –William DeWitt Alexander, reflecting on the "barbarism" that was apparently "cured" following the Western colonial coup overthrowing the government of Hawaii.

Although a little-known footnote today, Kamehameha V also began laying the groundwork for Kalākaua's Pacific Alliance. In 1871, Fiji had become a unified kingdom, and Charles St Julian was appointed by Hawaii to explore the feasibility of forming an alliance between Hawaii and Fiji. Unsurprisingly, Western powers did not allow Fiji to ponder this invitation for long—it was annexed by Britain in 1874. Decades prior, St Julian had been appointed by Kamehameha III as a commissioner to facilitate diplomacy between Hawaii and independent Pacific nations, and some historians cite him as a direct inspiration for Kalākaua's Pacific Alliance. St Julian died shortly after Fiji was annexed.

***

On his deathbed, Kamehameha V selected Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop as his heir; but she refused. Through familial relations, the heir presumptive was now Kamehameha V's cousin William Charles Lunalilo, but Kamehameha V refused to appoint him—knowing of his pro-Western sympathies.

"The throne belongs to Lunalilo; I will not appoint him, because I consider him unworthy of the position. The constitution, in case I make no nomination, provides for the election of the next King; let it be so." –Kamehameha V

Although the Constitution stated that the election of the monarch was to be carried out by the legislature, Lunalilo, wishing to expand democracy in the kingdom, convinced officials to hold a non-binding popular vote before the legislature formally selected the new monarch.

"Whereas, it is desirable that the wishes of the Hawaiian people be consulted as to a successor to the Throne, therefore, notwithstanding that according to the law of inheritance, I am the rightful heir to the Throne, in order to preserve peace, harmony and good order, I desire to submit the decision of my claim to the voice of the people." –Lunalilo's campaign slogan.

The main candidates in this election were Lunalilo (who emerged as the most popular due to his closer familial ties to Kamehameha V, and the charismatic declaration of his candidacy) and David Kalākaua. A favorite amongst hard-line anti-Westerners was Kamehameha V's half-sister and governor of Hawaii Island, Princess Ruth Keʻelikōlani.

Keʻelikōlani was an interesting character. Unlike other members of the Hawaiian royal family, who had become accustomed to luxurious Western palaces, Keʻelikōlani lived frugally in a standard stone and grass house—despite being one of the wealthiest Hawaiians due to her inheritance of the Kamehameha dynasty's estates. In addition to paying little mind to the bans on ancient Hawaiian spiritual practices, she even refused to speak English (despite being fluent) to resist the rapid incursion of Western cultural elements into Hawaiian society. Due to her mental, political, and physical strength (she was over 6 feet tall with an imposing frame!), she was frequently slandered by bitter Westerners.

Unfortunately, controversy over the legitimacy of Keʻelikōlani's genealogy made her too unpopular to gain many votes. Lunalilo won the popular vote by a large margin, and the legislature unanimously chose him (according to Queen Emma, out of fear that they would be lynched by angry mobs if they dared to go against the popular vote). Desiring to undo the Constitutional changes by his predecessor, he began to draft amendments to the constitution restoring the bicameral legislature, expanding suffrage, and requiring the monarch to write an explanation for any bill that was vetoed. Demonstrating his willingness to cozy up to Western powers, Lunalilo even went so far as to consider offering Pearl Harbor to the US in exchange for trading rights in order to achieve a temporary boost to the economy. (Understandably, Hawaiian citizens were outraged, and Lunalilo backtracked on this proposal). To further distance himself from his predecessors and the memory of their reigns, he was the first ruler not to take the name Kamehameha upon ascending the throne.

Although ruling for only one year and one month before his death, Lunalilo's pro-Western policies managed to cause a revolt within the army! After confronting the soldiers, he convinced them to end the revolt. In a bizarre blunder, Lunalilo subsequently disbanded the army, leaving Hawaii completely defenseless against Westerners who had a desire to annex Hawaii for decades...

V. King Kalākaua: A New Hope

Upon Lunalilo's death in 1874, both Emma Rooke and David Kalākaua declared their candidacies for monarch.

"To the Hawaiian Nation:

Salutations to You—Whereas His Majesty Lunalilo departed this life at the hour of nine o'clock last night; and by his death the Throne of Hawaii is left vacant, and the nation is without a head or a guide. In this juncture it is proper that we should seek for a Sovereign and Leader, and doing so, follow the course prescribed by Article 22nd of the Constitution. My earnest desire is for the perpetuity of the Crown and the permanent independence of the government and people of Hawaii, on the basis of the equity, liberty, prosperity, progress and protection of the whole people." –Kalākaua

Although not put up to a popular vote, it appears that Emma was quite popular with the populace at large, both due to her marriage to Kamehameha IV and the fact that Kalākaua did not belong to the Kamehameha dynasty which had been in power since Hawaii's unification. Despite the fact that both candidates were less pro-Western than Lunalilo had been, Emma was perceived as being sympathetic towards the British while Kalākaua was perceived as having pro-American sympathies. The Hawaiian legislature, likely due to the influence of a disproportionate number of US nationals within it, chose Kalākaua in a 39-6 vote. The result of the election caused riots in the streets of Honolulu, which embarrassingly had to be put down by US forces, since the Hawaiian military had been disbanded and the local police joined in the riots...

Anticipating the divisive effects that tyranny of the majority democracy would have on Hawaii, Kalākaua had been a strong critic of Lunalilo's pro-democracy sentiments during the earlier 1872 election. His fears were proven correct—the lynch mobs that many had feared would materialize after the 1872 election became a reality in the wake of the 1874 vote, injuring over a dozen legislators.

"O my people! My countrymen of old! Arise! This is the voice!

Ho! all ye tribes! Ho! my own ancient people! The people who took hold and built up the Kingdom of Kamehameha.

Arise! This is the voice.

Let me direct you, my people! Do nothing contrary to the law or against the peace of the Kingdom.

Do not go and vote.

Do not be led by the foreigners; they had no part in our hardships, in gaining the country. Do not be led by their false teachings." –Kalakaua, 1872

Despite the rocky start, Hawaiians would eventually warm up to Kalākaua. Eager to extend Hawaiian diplomatic and cultural connections around the globe, Kalākaua enacted a number of programs to this end. For example, a study abroad program was established and sent Hawaiians to study in Italy, Britain, the US, China, and Japan.

Although ubiquitous today due to the invention of air travel, Kalākaua was the first world leader to personally embark on a global diplomatic voyage. In 1881, he met with leaders from Japan, China, Thailand, Egypt, Italy, Britain, USA, and a number of others.

In addition to establishing new diplomatic ties and strengthening existing ones, he welcomed immigration from the nations he visited. Over the previous century, exposure to Western diseases had reduced Hawaii's population from high estimates of 800,000 to less than 100,000. In desperate need of manpower if Hawaii was to be able to support itself, Kalākaua set up a commission to determine which nations were either anti-Western or at least sympathetic to Hawaiian sovereignty, with the aim of encouraging immigration.

Kalākaua began transforming Hawaii into a cosmopolitan nation comparable to those of the New World. Immigrants came from China (who were banned from immigrating to the US under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882—which would not be repealed until 1943), Japan, and nations as far as Portugal. William Nevins Armstrong, who was appointed as Immigration Commissioner, corrupted by his Western prejudices, protested against allowing Indian and Muslim immigrants. Many Hawaiians found Armstrong's prejudice distasteful, and the King later sent Curtis P. Iaukea to India to reiterate that Hawaii welcomed all.

Not surprisingly, Western newspapers in the US and elsewhere were quick to whip up stories portraying Kalākaua's diplomatic voyage in a negative light, in order to delegitimize Hawaiian sovereignty. The most common story was that Kalākaua was "auctioning" Hawaiian sovereignty off to whichever nation would pay the highest price (with the added implication that US colonialists had better move in fast to snatch Hawaii up before Britain or other nations did!) The US Secretary of State and President apparently believed these rumors were credible enough to make clear to Britain that the US had first dibs on Hawaiian annexation. US nationals embedded in Hawaiian society had for decades been laboring to bring this annexationist dream into reality, and they would soon succeed...

***

Far superior to Kamehameha III's Minister of Foreign Affairs (the pro-annexation Robert Wyllie), Kalākaua appointed Walter M. Gibson. Gibson was an outspoken proponent of forming an anti-colonial confederacy in the Pacific and introduced many acts of legislation in order to strengthen diplomatic relations with the remaining independent Pacific nations.

Previously, on his global diplomatic voyage, Kalākaua had explored the possibility of uniting the kingdoms of Japan and Hawaii through marriage, but this suggestion was declined. Kalākaua then proposed a prototype of his Pacific Confederacy (which was also the spiritual forerunner, and possible inspiration of, Japan's later Co-Prosperity Sphere), offering for Japan to lead it. While this idea was also rejected, Kalākaua vividly understood the need for such anti-colonial alliance, and refined his plans over the coming years.

In 1883 Hawaii published a resolution condemning the colonization of the Pacific, and officially proclaimed that Hawaii viewed it as its duty to assist other non-Western states who desired to maintain independence:

“Whereas His Hawaiian Majesty’s Government being informed that certain Sovereign and Colonial States propose to annex various Islands and Archipelagoes of Polynesia, does hereby solemnly protest against such projects of annexation, as unjust to a simple and ignorant people, and subversive in their case of those conditions for favorable national development, which have been so happily accorded to the Hawaiian Nation.

The Hawaiian people, enjoying the blessings of national independence, confirmed by the joint action of great and magnanimous States, ever ready to afford favourable opportunities for self-government, cannot be silent about or indifferent to acts of intervention in contiguous and kindred groups, which menace our own situation.

The Hawaiian people, encouraged by favourable political conditions, have cultivated and entertained a strong national sentiment, which leads them not only to cherish their own political State, but also inspires them with a desire to have extended to kindred, yet less favoured, communities of Polynesia like favourable political opportunities for national development.

And whereas a Hawaiian Legislative Assembly, expressing unanimously the spirit of the nation, has declared that it was the duty of His Hawaiian Majesty's Government to proffer to kindred peoples and States of the Pacific an advising assistance to aid them in securing opportunities for improving their political and social condition: His Hawaiian Majesty's Government, responding to the national will, and to the especial appeals of several Polynesian Chiefs, has sent a Special Commissioner to several of the Polynesian Chieftains and States to advise them in their national affairs.

And His Hawaiian Majesty’s Government, speaking for the Hawaiian people, so happily prospering through national independence, makes earnest appeal to the Governments of great and enlightened States, that they will recognize the inalienable right of the several native communities of Polynesia to enjoy opportunities for progress and self-government, and will guarantee to them the same favourable political opportunities which have made Hawaii prosperous and happy, and which incite her national spirit to lift up a voice among the nations in behalf of sister islands and groups of Polynesia.”

(As it turned out, these "rights" were not inalienable, and within a few decades all of Oceania was colonized.)

***

A high-ranking military officer during Lunalilo's reign, Kalākaua was rumored to have helped incite the earlier anti-Western rebellion within the army. Early in Kalākaua's reign, he restored the military, and by the 1886 the military was modernized and expanded—rendering it quite formidable for a non-Western power.

The Hawaiian navy's modern warship, the HHMS Kaimiloa, set sail for Samoa in May 1887 as part of a mission to bring the Pacific Alliance into the next stage. It reached Apia Island in Samoa on June 16. Germany, the US, and UK, each hoping to annex Samoa as it was being destroyed by a civil war, had previously anchored warships in Apia harbor in early 1887, leading to a standoff known as the "Samoan Crisis". Although the HHMS Kaimiloa was by no means powerful enough on its own to have any hope of stopping the Westerners, it was a bold act which demonstrated not only to Samoa, but the world, that Kalākaua was serious about his alliance and serious about organizing resistance to Western colonialism.

On January 7, 1887, Hawaiian envoy John Bush had arrived in Samoa to discuss the Pacific alliance. King Laupepa of Samoa formally accepted this alliance on February 17, and the treaty was ratified in Hawaii on March 21st. The Kaimiloa's arrival signaled that this alliance was not merely a pleasantry with no hopes of actually being manifested, but moving full steam ahead. News of the treaty was forwarded to the Western powers keeping an eye on Samoa, with the additional announcement that envoys would soon be sent to Tonga, the Cook Islands, Tuvalu, and the Gilbert Islands (Kiribati) to invite them to the alliance.

Germany, who had been funding King Laupepa's opponent in a civil war which started in 1886, nearly started a war with Hawaii, outraged at their "meddling" in Samoan affairs.

"In case Hawaii, whose King acts according to financial principles which it is not desirable to extend to Samoa, should try to interfere in favor of Malietoa [King Laupepa], the King of the Sandwich Islands would thereby enter into a state of war with us." –Bismarck, giving instructions of the German Minister at Washington

***

Shocked by Hawaii's growing international power and the implications that an alliance between Samoa and Hawaii could have for future colonial aspirations in the Pacific, a coup against King Kalākaua (utilizing Western agents who had infiltrated and taken control of the Honolulu Rifles during the military's expansion in 1886) began on June 30, and culminated with the King's forced signing of the "Bayonet Constitution" on July 6, 1887.

Drafted by a secret society of pro-annexation Westerners, the Bayonet Constitution greatly empowered the legislature, drastically limited the monarch's ability to appoint officials, and allowed non-citizens to vote (which, along with wealth requirements, ensured Western elites gained a stranglehold on the electorate).

The legislature was now able to appoint and remove the monarch's cabinet officials with minimal input from the monarch. Gibson was ousted and almost hanged. Continuing to fear for his life, he fled the country and died in 1888. Surrounded by hardline Westerners and in fear of assassination should he protest, Kalākaua's reign had essentially come to an end.

After the coup, Kalākaua's expansion of the military was conveniently found "unconstitutional" and the Kaimiloa was recalled on August 23, being decommissioned on August 30 after completing its only voyage.

Apparently not respecting the idea that non-Western nations had the ability to have formal diplomatic relations with other non-Western nations, the existence of the alliance between Hawaii and Samoa was ignored by Western powers after the coup. Unable to compete in an open war against Germany, the US, and UK (and after suffering a coup drastically reducing the King's power) Hawaii did not continue to pursue this alliance. Ravaged by political instability and multiple civil wars funded by Germany, the US, and UK, Samoa also seemed to give up hope. Samoa nominally remained independent until it was annexed by Germany and the US in December 1899. Ironically, this annexation resulted in Hawaii and Samoa being united once again...

***

The Bayonet Constitution cut many state-sponsored programs. Among these was the study abroad program. Students of these programs—including Robert William Wilcox, who had been studying military strategy in Italy—were recalled back to Hawaii.

Despite the obvious fact that the Bayonet Constitution was designed to specifically limit the power of the monarch, Wilcox blamed Kalākaua for the unraveling of Hawaiian society in the years after the Constitution was implemented. Viewing Kalākaua as too weak to lead (despite his prior diplomatic accomplishments establishing friendship with other Pacific nations), Wilcox plotted to replace the King with his sister, Liliʻuokalani. Wilcox was unable to carry out this plan, as it was discovered two days before its planned implementation. He subsequently fled to the United States.

The next year, in 1889, Wilcox followed through with a new plan. Apparently realizing the flaw in his original scheme (replacing the monarch but not the constitution which limited their power in the first place!), he planned to force Kalākaua to reinstate the Constitution of 1864—thereby restoring power to the monarch. While one might assume that Kalākaua would be pleased to have his powers restored, Wilcox's self-interest had set his plans up for failure.

Kalākaua was aware that rebels had conspired to replace him with his sister the year before and, especially after the imposition of the Bayonet Constitution, he was on high alert for any suspicious activity. Kalākaua had somehow received word that a rebellion was imminent and avoided his palace—fearing the rebels once again planned to depose or assassinate him.

After a fierce fight against both palace guards and the Honolulu Rifles, Wilcox's forces surrendered. He was tried for treason, but acquitted by a jury who was sympathetic to what they perceived as an act of defiance against the Western oligarchs controlling the nation. Had Kalākaua known that Wilcox did not intend to overthrow him, the rebellion may have turned out differently. In any case, it mattered little, as Kalākaua died soon after in 1891.

***

As monumental as King Kalākaua's achievements were to Hawaii and the entire Pacific, it was too little too late, and his reign was bogged down by many strategic miscalculations. It is certainly easy in hindsight to point out the various bits of Kalākaua's reign that were sure to lead to disastrous effects—but we must not be too uncharitable in our estimation, as Hawaii's options at the time rapidly diminished with each passing year. Even so, these mistakes should not lessen the inspiration that Hawaiians and citizens of the Pacific islands can gain from Kalākaua's genuinely positive vision of a Pacific Basin united against Western tyranny. But Hawaiian history is incomplete without an honest examination of Hawaii's downfall as a sovereign nation. If the vision of a united Pacific is to ever be realized, we cannot make the same errors.

VI. The Sun Sets on Hawaii

Just as Japan realized that it would be difficult to directly compete against Western nations unless it began Westernizing its economy, Hawaii also gave into this pressure. In 1875 a trade agreement was signed between the US and Hawaii which led to huge investments in the Hawaiian sugarcane industry by US speculators. While this treaty led to an over 7-fold increase in the amount of trade income over the course of Kalākaua's reign, it was not without dire consequences. The Hawaiian government had always been heavily influenced by Westerners, all the way back to the latter days of Kamehameha I's reign, but the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 tightened the noose to such an extent that Hawaii would not be able to escape. In the years after the treaty, Western speculation exploded—to give one example, Claus Spreckels came to control 1/3 of the sugar industry in Hawaii. (Although loyal to the monarchy, Spreckels became so powerful that he frequently loaned money to the King; an unpleasant position which Kalākaua only got out of by paying Spreckels off with a loan from a London bank...) Even worse, the renewal of the treaty added additional terms giving the US exclusive use of Pearl Harbor—something which even the thoroughly pro-Western Lunalilo did not dare to pursue.

"I take great pleasure in informing you that the Treaty of Reciprocity with the United States of America has been definitely extended for seven years upon the same terms as those in the original treaty, with the addition of a clause granting to national vessels of the United States the exclusive privilege of entering Pearl River Harbor and establishing there a coaling and repair station. This has been done after mature deliberation and the interchange between my Government and that of the United States of an interpretation of the said clause whereby it is agreed and understood that it does not cede any territory or part with or impair any right of sovereignty or jurisdiction on the part of the Hawaiian Kingdom and that such privilege is coterminous with the treaty. I regard this as one of the most important events of my reign, and I sincerely believe that it will re-establish the commercial progress and prosperity which began with the Reciprocity Treaty." –King Kalakaua, 1887

Supporters of Queen Emma now had solid proof of the dangers of Kalakaua's ties to the US. One of the politicians who voted for Emma, Joseph Nāwahī, correctly predicted the 1875 treaty would be "a nation-snatching treaty" and "the first step of annexation." Of course, this is not to say that had Emma been elected, Hawaii couldn't have suffered the same fate, but at the hands of the British. Afterall, in 1877 Britain created the Western Pacific High Commission, setting the stage for their colonial expansion in the Pacific. This came shortly after Fiji, one of the last significant independent Oceanic nations other than Hawaii, was annexed in 1874.

“...they could dispose of their sugar to a much greater advantage in the free trade ports of Australia, the Hawaiian planters were preparing to send thither their whole crop of 1875-6. Sugar was the chief export of the Islands, and with this sugar they had bought manufactured goods in the United States. But if on account of the United States tariff on sugar this trade was diverted into English ports and was carried on in English vessels, the Hawaiians would no longer be bound by commercial ties to the United States, and the island trade would certainly drift to English control, and the Islands themselves would in time become a dependency of Great Britain. It was this knowledge that secured favorable consideration for a reciprocity treaty whose fate without it would have been problematical at least.” –Chalfant Robinson, 1903. US author explaining why the US was eager to sign the Reciprocity Treaty.

***

Although he made significant contributions to Hawaiian policy by advocating independence and helping to facilitate interest in the Pacific Confederacy, Walter M. Gibson had quite the reputation of being a flamboyant glory-seeker. According to some reports, Gibson seems to have had what we today call a "white savior complex"—he sought fame not from overthrowing non-Western nations, but by offering his apparently superior skills and knowledge to help "save" the pitiable "noble savages" from Western influence.

While likely sincere in his calls for hardline anti-colonialism in the Pacific, he regrettably encouraged the King to engage in grandiose and often wasteful projects in order to increase the pomp of Hawaii on the world stage. On his world tour, Kalākaua had become impressed with the European military pageantry and the luxurious palaces of other monarchs. This led to an expensive reconstruction of ʻIolani Palace and a grand coronation ceremony in 1883 (due to the riots after his election, the original swearing in ceremony was kept short and simple).

Lavish spending and similarly outspoken anti-colonialist opinions from other ministers such as Celso Caesar Moreno allowed Westerners to argue the Hawaiian government was not sufficiently "mature" or proper enough to be allowed to continue on the global stage. Under the surface, however, they were motivated by the fear of what Hawaii and the Pacific could become if they were allowed to remain as a global voice of anti-colonial resistance.

" ... uniting under your sceptre the whole Polynesian race and make Honolulu a monarchical Washington, where the representatives of all the islands would convene in Congress." –Celso Caesar Moreno

***

After the imposition of the Bayonet Constitution Kalākaua lived a lonely life. Under constant surveillance and betrayed by many who were once close to him, his sister (future Queen Liliʻuokalani) was one of the few people he could confide in. He died while abroad in the US in 1891, and was given a funeral in San Fransisco which attracted over 100,000 spectators.

Hawaiian romanticists maintain that Kalākaua's last words were "Tell my people I tried."

And thus concluded another chapter of this tragic history.